Discover the comprehensive nursing care planning guide for hypertension (HTN), encompassing common nursing diagnoses. Explore nursing assessments, interventions, rationales, teaching strategies, and goals to effectively manage HTN.

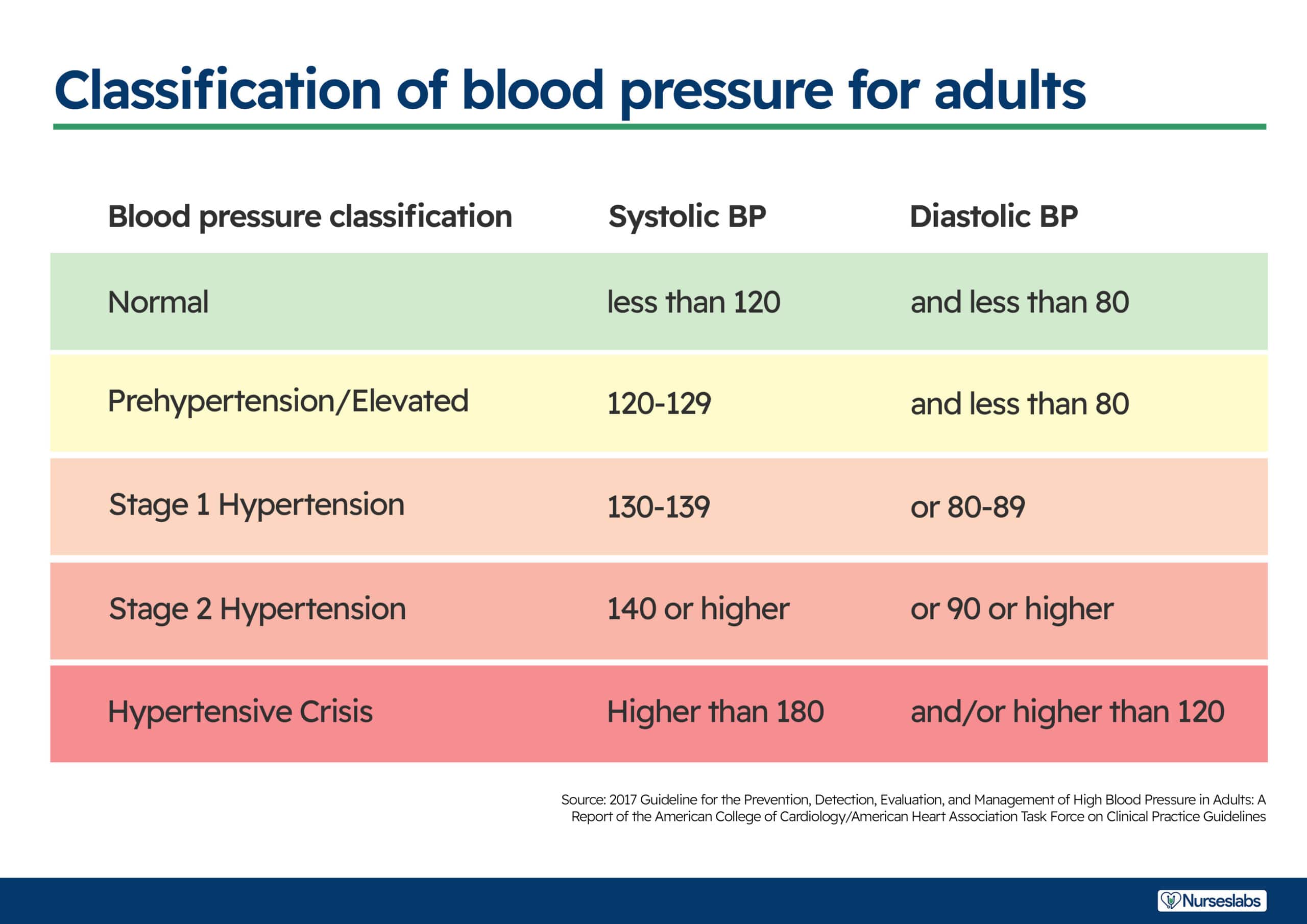

Hypertension is the term used to describe high blood pressure. Hypertension is repeatedly elevated blood pressure exceeding 140 over 90 mmHg. It is categorized as primary or essential (approximately 90% of all cases) or secondary due to an identifiable, sometimes correctable pathological condition, such as renal disease or primary aldosteronism.

Blood pressure is determined by the interaction of cardiac output and peripheral resistance. Hypertension can result from increased cardiac output, increased peripheral resistance, or both. Various factors contribute to hypertension, including increased sympathetic nervous system activity, renal sodium reabsorption, activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, impaired vasodilation, insulin resistance, and immune response activation.

Hypertension often presents with no physical abnormalities except for elevated blood pressure. However, retinal changes like hemorrhages, fluid accumulation, and narrowing of blood vessels may occur. In severe cases, swelling of the optic disc (papilledema) can be observed. While many individuals with hypertension remain asymptomatic for a long time, the appearance of specific signs and symptoms indicates vascular damage. This can manifest as angina, myocardial infarction, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, kidney dysfunction, nocturia, and cerebrovascular complications such as transient ischemic attacks or strokes.

Nursing care management and care plans are essential for patients with hypertension as they provide structured guidance for nurses to assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions tailored to the patient’s needs. These plans help monitor blood pressure, promote medication adherence, and provide education on lifestyle modifications, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

The following are the nursing priorities for patients with hypertension:

Thorough health history, physical examination, retinal assessment, and laboratory tests are crucial for evaluating hypertension and identifying target organ damage. Risk factor assessment guides treatment for cardiovascular complications

Assess for the following subjective and objective data:

Assess for factors related to the cause of hypertension:

Nursing diagnoses provide a standardized method for recognizing, prioritizing, and addressing specific client needs and responses in relation to hypertension, including both actual and high-risk problems. They encompass the identification of current or potential health issues that can be effectively prevented or resolved through independent nursing interventions. Formulating nursing diagnoses becomes essential after conducting a thorough assessment to effectively address the patient’s current and potential health concerns related to hypertension. These diagnoses serve as a framework for developing and implementing personalized nursing interventions, aiming to optimize patient care. For example:

Goals and expected outcomes may include:

Nursing care for hypertension aims to lower and control blood pressure effectively, safely, and economically. The nurse plays a vital role in supporting and educating patients about lifestyle modifications, medication adherence, and regular follow-up to monitor progress and address any potential complications.

Blood pressure is the product of cardiac output multiplied by peripheral resistance. Hypertension can result from an increase in cardiac output (heart rate multiplied by stroke volume), an increase in peripheral resistance, or both.

Review clients at risk and individuals with conditions that stress the heart.

Persons with acute or chronic conditions may compromise circulation and place excessive demands on the heart.

Check laboratory data (cardiac markers, complete blood cell count, electrolytes, ABGs, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, cardiac enzymes, and cultures, such as blood, wound, or secretions).

To identify contributing factors.

Monitor and record BP. Measure in both arms and thighs three times, 3–5 min apart while the patient is at rest, then sitting, then standing for initial evaluation. Use correct cuff size and accurate technique. Comparison of pressures provides a complete picture of vascular involvement or the scope of the problem. Severe hypertension is classified in adults as a diastolic pressure elevation of 110 mmHg; progressive diastolic readings above 120 mmHg are considered first accelerated, then malignant (very severe). Systolic hypertension is also an established risk factor for cerebrovascular disease and ischemic heart disease when elevated diastolic pressure. See updated guidelines for classifying hypertension above.

Note the presence, and quality of central and peripheral pulses.

Bounding carotid, jugular, radial, and femoral pulses may be observed and palpated. Pulses in the legs and feet may be diminished, reflecting the effects of vasoconstriction (increased systemic vascular resistance [SVR]) and venous congestion.

Auscultate heart tones and breath sounds.

S4 heart sound is common in severely hypertensive patients because of atrial hypertrophy (increased atrial volume and pressure). Development of S3 indicates ventricular hypertrophy and impaired functioning. The presence of crackles and wheezes may indicate pulmonary congestion secondary to developing or chronic heart failure.

Observe skin color, moisture, temperature, and capillary refill time.

The presence of pallor; cool, moist skin; and delayed capillary refill time may be due to peripheral vasoconstriction or reflect cardiac decompensation and decreased output.

Note dependent and general edema.

May indicate heart failure, renal, or vascular impairment.

Evaluate client reports or evidence of extreme fatigue, intolerance for activity, sudden or progressive weight gain, swelling of extremities, and progressive shortness of breath.

To assess for signs of poor ventricular function or impending cardiac failure.

Provide calm, restful surroundings, and minimize environmental activity and noise. Limit the number of visitors and length of stay.

It helps lessen sympathetic stimulation; promotes relaxation.

Maintain activity restrictions (bedrest or chair rest); schedule uninterrupted rest periods; assist patient with self-care activities as needed.

Lessens physical stress and tension that affect blood pressure and the course of hypertension.

Provide comfort measures (back and neck massage, the elevation of head).

Decreases discomfort and may reduce sympathetic stimulation.

Instruct in relaxation techniques, guided imagery, and distractions.

Can reduce stressful stimuli, and produce a calming effect, thereby reducing BP.

Administer medications and monitor response to medications to control blood pressure.

Response to drug therapy (usually consisting of several drugs, including diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, vascular smooth muscle relaxants, and beta and calcium channel blockers) is dependent on both the individual and the synergistic effects of the drugs. Because of side effects, drug interactions, and patient’s motivation for taking antihypertensive medication, it is important to use the smallest number and lowest dosage of medications.

Prepare for surgery when indicated.

When hypertension is due to pheochromocytoma, removal of the tumor will correct the condition.

Hypertension medications reduce blood pressure by targeting various factors. Initial treatment options depend on patient characteristics, such as age and ethnicity. Medications are started at low doses and adjusted as needed to achieve blood pressure control. Simplifying the treatment regimen promotes adherence, ideally with once-daily combination pills. Gradual dose reduction may be considered once blood pressure is well-controlled.

Thiazide diuretics: chlorothiazide (Diuril); hydrochlorothiazide (Esidrix/HydroDIURIL); bendroflumethiazide (Naturetin); indapamide (Lozol); metolazone (Diulo); quinethazone (Hydromox).

Diuretics are considered first-line medications for uncomplicated stage I or II hypertension and may be used alone or in association with other drugs (such as beta-blockers) to reduce BP in patients with relatively normal renal function. These diuretics potentiate the effects of other antihypertensive agents as well, by limiting fluid retention, and may reduce the incidence of strokes and heart failure.

Loop diuretics: furosemide (Lasix); ethacrynic acid (Edecrin); bumetanide (Bumex), torsemide (Demadex).

These drugs produce marked diuresis by inhibiting reabsorption of sodium and chloride and are effective antihypertensives, especially in patients who are resistant to thiazides or have renal impairment.

Potassium-sparing diuretics: spironolactone (Aldactone); triamterene (Dyrenium); amiloride (Midamor).

May be given in combination with a thiazide diuretic to minimize potassium loss.

Alpha, beta, or centrally acting adrenergic antagonists: doxazosin (Cardura); propranolol (Inderal); acebutolol (Sectral); metoprolol (Lopressor), labetalol (Normodyne); atenolol (Tenormin); nadolol (Corgard), carvedilol (Coreg); methyldopa (Aldomet); clonidine (Catapres); prazosin (Minipress); terazosin (Hytrin); pindolol (Visken).

Beta-Blockers may be ordered instead of diuretics for patients with ischemic heart disease; obese patients with cardiogenic hypertension; and patients with concurrent supraventricular arrhythmias, angina, or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Specific actions of these drugs vary, but they generally reduce BP through the combined effect of decreased total peripheral resistance, reduced cardiac output, inhibited sympathetic activity, and suppression of renin release. Note: Patients with diabetes should use Corgard and Visken with caution because they can prolong and mask the hypoglycemic effects of insulin. The elderly may require smaller doses because of the potential for bradycardia and hypotension. African-American patients tend to be less responsive to beta-blockers in general and may require increased dosage or use of another drug (monotherapy with a diuretic).

Calcium channel antagonists: nifedipine (Procardia); verapamil (Calan); diltiazem (Cardizem); amlodipine (Norvasc); isradipine (DynaCirc); nicardipine (Cardene).

May be necessary to treat severe hypertension when a combination of a diuretic and a sympathetic inhibitor does not sufficiently control BP. Vasodilation of healthy cardiac vasculature and increased coronary blood flow are secondary benefits of vasodilator therapy.

Adrenergic neuron blockers: guanadrel (Hylorel); guanethidine (Ismelin); reserpine (Serpalan).

Reduce arterial and venous constriction activity at the sympathetic nerve endings.

Direct-acting oral vasodilators: hydralazine (Apresoline); minoxidil (Loniten).

Action is to relax vascular smooth muscle, thereby reducing vascular resistance.

Direct-acting parenteral vasodilators: diazoxide (Hyperstat), nitroprusside (Nitropress); labetalol (Normodyne).

These are given intravenously for the management of hypertensive emergencies.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: captopril (Capoten); enalapril (Vasotec); lisinopril (Zestril); fosinopril (Monopril); ramipril (Altace). Angiotensin II blockers: valsartan (Diovan), guanethidine (Ismelin).

The use of an additional sympathetic inhibitor may be required for its cumulative effect when other measures have failed to control BP or when congestive heart failure (CHF) or diabetes is present.

Analgesics; Antianxiety agents: lorazepam (Ativan), alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium).

Reduce or control pain and decrease stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. May aid in the reduction of tension and discomfort that is intensified by stress.

Hypertension can cause decreased activity tolerance due to cardiac output changes and medication side effects. Nurses play a vital role in assessing and addressing this issue, implementing interventions to improve patients’ ability to engage in activities and manage their hypertension.

Note the presence of factors contributing to fatigue (age, frail, acute or chronic illness, heart failure, hypothyroidism, cancer, and cancer therapies).

Fatigue affects both the client’s actual and perceived ability to participate in activities.

Evaluate the client’s actual and perceived limitations or degree of deficit in light of usual status.

Provides a comparative baseline and provides information about needed education and interventions regarding the quality of life.

Assess the patient’s response to activity.

Noting pulse rate more than 20 beats per min faster than resting rate; marked increase in BP during and after activity (systolic pressure increase of 40 mm Hg or diastolic pressure increase of 20 mm Hg); dyspnea or chest pain; excessive fatigue and weakness; diaphoresis; dizziness or syncope. The stated parameters help assess physiological responses to the stress of activity and, if present, are indicators of overexertion.

Assess emotional and psychological factors affecting the current situation.

Stress or depression may be increasing the effects of an illness, or depression might be the result of being forced into inactivity.

Instruct patient in energy-conserving techniques (using a chair when showering, sitting to brush teeth or comb hair, carrying out activities at a slower pace).

Energy-saving techniques reduce energy expenditure, thereby assisting in the equalization of oxygen supply and demand.

Encourage progressive activity and self-care when tolerated. Assist as needed.

Gradual activity progression prevents a sudden increase in cardiac workload. Providing assistance only as needed encourages independence in performing activities.

Elevation in resting blood pressure means a progressive reduction in sensitivity to acute pain, which could result in a tendency to restore arousal levels in the presence of painful stimuli.

Note the client’s attitude toward pain and use of pain medications, including any history of substance abuse.

To assess etiology or precipitating contributory factors.

Determine specifics of pain (location, characteristics, intensity (0–10 scale), onset, and duration). Note nonverbal cues.

Facilitates diagnosis of problem and initiation of appropriate therapy. Helpful in evaluating the effectiveness of therapy.

Encourage and maintain bed rest during the acute phase.

Minimizes stimulation and promotes relaxation.

Provide or recommend non pharmacological measures to relieve headache such as cool cloth to forehead; back and neck rubs; quiet, dimly lit room; relaxation techniques (guided imagery, distraction); and diversional activities.

Measures that reduce cerebral vascular pressure and slow or block sympathetic response effectively relieve headaches and associated complications.

Eliminate or minimize vasoconstricting activities that may aggravate headache (straining at stool, prolonged coughing, bending over).

Activities that increase vasoconstriction accentuate the headache in the presence of increased cerebral vascular pressure.

Assist patient with ambulation as needed.

Dizziness and blurred vision frequently are associated with vascular headaches. The patient may also experience episodes of postural hypotension, causing weakness when ambulating.

Provide liquids, soft foods, and frequent mouth care if nosebleeds occur, or nasal packing has been done to stop bleeding.

Promotes general comfort. Nasal packing may interfere with swallowing or require mouth breathing, leading to stagnation of oral secretions and drying of mucous membranes.

Administer analgesics medications as indicated.

See pharmacological interventions.

Non adherence from therapeutic program is common in hypertension management. Medication discontinuation is high, and blood pressure control rates are low. Patient adherence improves with self-care involvement, including self-monitoring and tailored wellness programs. Effort is required for lifestyle modifications and medication adherence. Nurses play a vital role in supporting behavior change and providing follow-up care.

Determine individual stressors (family, social, work environment, life changes, or healthcare management).

To evaluate the degree of impairment.

Evaluate ability to understand events, provide a realistic appraisal of the situation.

To evaluate the degree of impairment.

Assess the effectiveness of coping strategies by observing behaviors (ability to verbalize feelings and concerns, willingness to participate in the treatment plan).

Adaptive mechanisms are necessary to appropriately alter one’s lifestyle, deal with the chronicity of hypertension, and integrate prescribed therapies into daily living.

Note reports of sleep disturbances, increasing fatigue, impaired concentration, irritability, decreased tolerance of headache, inability to cope or problem-solve.

Manifestations of maladaptive coping mechanisms may be indicators of repressed anger and be major determinants of diastolic BP.

Implement dietary sodium, fat, and cholesterol restrictions as indicated.

These restrictions can help manage fluid retention and, with the associated hypertensive response, decrease myocardial workload.

Assist the patient in identifying specific stressors and possible strategies for coping with them. Recognition of stressors is the first step in altering one’s response to the stressor.

Include the patient in care planning and encourage maximum participation in the treatment plan.

Involvement provides the patient with an ongoing sense of control, improves coping skills, and can enhance cooperation with the therapeutic regimen.

Encourage the patient to evaluate life priorities and goals. Ask questions such as “Is what you are doing getting you what you want?”

Focuses patient’s attention on the reality of present situation relative to patient’s view of what is wanted. Strong work ethic, need for “control,” and outward focus may have led to a lack of attention to personal needs.

Assist the patient in identifying and begin planning for necessary lifestyle changes. Assist in adjusting, rather than abandon, personal/family goals.

Necessary changes should be realistically prioritized so patients can avoid being overwhelmed and feeling powerless.

Help client to substitute positive thoughts for negative ones such as ” I can do this; I am in charge of myself.”

To provide meeting psychological needs.

In hypertension nursing care, emphasizing weight reduction and lifestyle changes is vital. Educating patients about the impact of weight on blood pressure and promoting healthy habits helps control hypertension and improve cardiovascular health.

Assess risk or presence of conditions associated with obesity

Obesity is an added risk with high blood pressure because of the disproportion between fixed aortic capacity and increased cardiac output associated with increased body mass. Many studies have shown that weight loss is frequently associated with a decrease in blood pressure.

Assess the meaning and significance of food in the patient’s life.

The patient’s attitude towards food implicitly determines their choices between healthy and unhealthy foods.

Assess patient understanding of the direct relationship between hypertension and obesity.

Weight reduction may obviate the need for drug therapy or decrease the medication needed to control BP. Dysfunctional eating habits contribute to atherosclerosis and obesity, which predispose to hypertension – ultimately complications such as stroke, kidney disease, and heart failure.

Problem-solve with the patient to identify ways appropriate lifestyle changes can reduce modifiable risk factors.

Changing “comfortable or usual” behavior patterns can be complicated and stressful. Support, guidance, and empathy can enhance patient’s success in accomplishing these tasks.

Determine the patient’s desire to lose weight.

Readiness and motivation to change for weight reduction is an important part of treatment for behavior change. The individual should be ready to lose weight, or the program will most likely not succeed.

Assess the patient’s current nutritional status by using a food diary.

Insightful to examine the usual foods eaten and the patient’s pattern of eating. Self-monitoring apps are also useful and convenient.

Review usual daily caloric intake and dietary choices.

Identifies current strengths and weaknesses in the dietary program—aids in determining the individual need for adjustment and teaching.

Establish a realistic weight-reduction plan with the patient, such as 1 lb weight loss per wk.

Reducing caloric intake by 500 calories daily theoretically yields a weight loss of 1 lb per wk. Therefore, a slow weight reduction indicates fat loss with muscle-sparing and generally reflects a change in eating habits.

Encourage the patient to maintain a diary of food intake, including when and where eating takes place and the circumstances and feelings around which the food was eaten.

Provides a database for both the adequacy of nutrients eaten and the emotional conditions of eating. It helps focus attention on factors that the patient has control over or can change.

Discuss the necessity for decreased caloric intake and limited fats, salt, and sugar as indicated.

Excessive salt intake expands the intravascular fluid volume and may damage kidneys, which can further aggravate hypertension. Restriction on salt intake and lowering intake of saturated fats and cholesterol helps in reducing body weight.

Instruct and assist in appropriate food selections, such as a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods referred to as the DASH Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and avoiding foods high in saturated fat (butter, cheese, eggs, ice cream, meat) and cholesterol (fatty meat, egg yolks, whole dairy products, shrimp, organ meats).

Avoiding foods high in saturated fat and cholesterol is important in preventing progressing atherogenesis. Moderation and use of low-fat products in place of total abstinence from certain food items may prevent a sense of deprivation and enhance cooperation with the dietary regimen. In conjunction with exercise, weight loss, and limits on salt intake, the DASH diet may reduce or even eliminate the need for drug therapy.

Recommend patient to eat a well-balanced, healthy breakfast every morning.

Skipping breakfast will likely cause the patient to overeat during the evening.

Refer to a dietitian as indicated.

Can provide additional counseling and assistance with meeting individual dietary needs.

In nursing, educating patients with hypertension is vital as it empowers them to understand their condition, make informed choices, and actively participate in their care. By providing knowledge on hypertension causes, risk factors, and management, nurses help patients adhere to medications, adopt healthy lifestyles, and monitor blood pressure. This education promotes patient empowerment, better outcomes, and improved quality of life.

Assess readiness and blocks to learning. Include significant other (SO).

Misconceptions and denial of the diagnosis because of long-standing feelings of well-being may interfere with the patient and SO willingness to learn about the disease, progression, and prognosis. If the patient does not accept the reality of a life-threatening condition requiring continuing treatment, lifestyle and behavioral changes will not be initiated or sustained.

Define and state the limits of desired BP. Explain hypertension and its effects on the heart, blood vessels, kidneys, and brain.

Provides the basis for understanding elevations of BP and clarifies frequently used medical terminology. Understanding that high BP can exist without symptoms is central to enabling the patient to continue treatment, even when feeling well.

Avoid saying “normal” BP, and use the term “well-controlled” to describe the patient’s BP within desired limits.

Because treatment for hypertension is lifelong, conveying the idea of “control” helps the patient understand the need for continued treatment and medication.

Assist patient in identifying modifiable risk factors (obesity; a diet high in sodium, saturated fats, and cholesterol; sedentary lifestyle; smoking; alcohol intake of more than 2 oz per day regularly; stressful lifestyle).

These risk factors have been shown to contribute to hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease.

Discuss the importance of eliminating smoking, and assist the patient in formulating a plan to quit smoking.

Nicotine increases catecholamine discharge, resulting in increased heart rate, BP, vasoconstriction, and myocardial workload, and reduces tissue oxygenation.

Reinforce the importance of adhering to treatment regimens and keeping follow-up appointments.

Lack of cooperation is a common reason for the failure of antihypertensive therapy. Therefore, ongoing evaluation for patient cooperation is critical to successful treatment. Compliance usually improves when the patient understands the causative factors and consequences of inadequate intervention and health maintenance.

Instruct and demonstrate the technique of BP self-monitoring. Evaluate patient’s hearing, visual acuity, manual dexterity, and coordination.

Monitoring BP at home is reassuring to patients because it provides visual and positive reinforcement for following the medical regimen and promotes early deleterious changes.

Help patients develop a simple, convenient schedule for taking medications.

Individualizing medication schedules to fit the patient’s personal habits and needs may facilitate cooperation with the long-term regimen.

Explain prescribed medications along with their rationale, dosage, expected and adverse side effects, and idiosyncrasies

Adequate information and understanding that side effects (mood changes, initial weight gain, dry mouth) are common and often subside with time can enhance cooperation with a treatment plan.

Diuretics: Take daily doses (or larger doses) in the early morning.

Scheduling minimizes nighttime urination.

Weigh self on a regular schedule and record;

The primary indicator of the effectiveness of diuretic therapy.

Avoid or limit alcohol intake.

The combined vasodilating effect of alcohol and the volume-depleting effect of a diuretic greatly increase the risk of orthostatic hypotension.

Notify physician if unable to tolerate food or fluid;

Dehydration can develop rapidly if intake is poor and the patient continues to take a diuretic.

Antihypertensives: Take prescribed doses regularly; avoid skipping, altering, or making up doses; and do not discontinue without notifying the healthcare provider. Review potential side effects and/or drug interactions;

Because patients often cannot feel the difference the medication makes in blood pressure, it is critical to understand the medications’ working and side effects. For example, abruptly discontinuing a drug may cause rebound hypertension leading to severe complications, or medication may be altered to reduce adverse effects.

Rise slowly from a lying to a standing position, sitting for a few minutes before standing. Sleep with the head slightly elevated.

Measures reduce the severity of orthostatic hypotension associated with the use of vasodilators and diuretics.

Suggest frequent position changes, leg exercises when lying down.

Decreases peripheral venous pooling that may be potentiated by vasodilators and prolonged sitting/standing.

Recommend avoiding hot baths, steam rooms, and saunas, especially with the concomitant use of alcoholic beverages.

Prevents vasodilation with the potential for dangerous side effects of syncope and hypotension.

Instruct patient to consult a healthcare provider before taking other prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) medications.

Precaution is important in preventing potentially dangerous drug interactions. Any drug that contains a sympathetic nervous stimulant may increase BP or counteract antihypertensive effects.

Instruct patient about increasing intake of foods/ fluids high in potassium (oranges, bananas, figs, dates, tomatoes, potatoes, raisins, apricots, Gatorade, and fruit juices and foods/ fluids high in calcium such as low-fat milk, yogurt, or calcium supplements, as indicated).

Diuretics can deplete potassium levels. Dietary replacement is more palatable than drug supplements and maybe all that is needed to correct the deficit. Some studies show that 400 mg of calcium per day can lower systolic and diastolic BP. Correcting mineral deficiencies can also affect BP.

Review signs and symptoms requiring notification of healthcare provider (headache present on awakening that does not abate; sudden and continued increase of BP; chest pain, shortness of breath; irregular or increased pulse rate; significant weight gain (2 lb per day or 5 lb per wk) or peripheral and abdominal swelling; visual disturbances; frequent, uncontrollable nosebleeds; depression or emotional lability; severe dizziness or episodes of fainting; muscle weakness or cramping; nausea/ vomiting; excessive thirst.

Early detection of developing complications, decreased effectiveness of drug regimen, or adverse reactions to it allow for timely intervention.

Explain the rationale for the prescribed dietary regimen (usually a diet low in sodium, saturated fat, and cholesterol).

Excess saturated fats, cholesterol, sodium, alcohol, and calories have been defined as nutritional risks in hypertension. A diet low in fat and high in polyunsaturated fat reduces BP, possibly through prostaglandin balance in both normotensive and hypertensive people.

Help patient identify sources of sodium intake (table salt, salty snacks, processed meats and cheeses, sauerkraut, sauces, canned soups and vegetables, baking soda, baking powder, monosodium glutamate). Stress the importance of reading ingredient labels of foods and OTC drugs.

Two years on a moderate low-salt diet may be sufficient to control mild hypertension or reduce the amount of medication required.

Encourage the patient to establish an individual exercise program incorporating aerobic exercise (walking, swimming) within the patient’s capabilities. Stress the importance of avoiding isometric activity.

Besides helping to lower BP, aerobic activity aids in toning the cardiovascular system. Isometric exercise can increase serum catecholamine levels, further elevating BP.

Demonstrate application of ice pack to the back of the neck and pressure over the distal third of the nose, and recommend that patient lean the head forward if nosebleed occurs.

Nasal capillaries may rupture as a result of excessive vascular pressure. Cold and pressure constrict capillaries to slow or halt bleeding. Leaning forward reduces the amount of blood that is swallowed.

Provide information regarding community resources, and support the patient in making lifestyle changes. Initiate referrals as indicated.

Community resources such as the American Heart Association, “coronary clubs,” stop smoking clinics, alcohol (drug) rehabilitation, weight loss programs, stress management classes, and counseling services may be helpful in patient’s efforts to initiate and maintain lifestyle changes.

Recommended nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan books and resources.

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy.

Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing Diagnosis Handbook: An Evidence-Based Guide to Planning Care

We love this book because of its evidence-based approach to nursing interventions. This care plan handbook uses an easy, three-step system to guide you through client assessment, nursing diagnosis, and care planning. Includes step-by-step instructions showing how to implement care and evaluate outcomes, and help you build skills in diagnostic reasoning and critical thinking.

Nursing Care Plans – Nursing Diagnosis & Intervention (10th Edition)

Includes over two hundred care plans that reflect the most recent evidence-based guidelines. New to this edition are ICNP diagnoses, care plans on LGBTQ health issues, and on electrolytes and acid-base balance.

Nurse’s Pocket Guide: Diagnoses, Prioritized Interventions, and Rationales

Quick-reference tool includes all you need to identify the correct diagnoses for efficient patient care planning. The sixteenth edition includes the most recent nursing diagnoses and interventions and an alphabetized listing of nursing diagnoses covering more than 400 disorders.

Nursing Diagnosis Manual: Planning, Individualizing, and Documenting Client Care

Identify interventions to plan, individualize, and document care for more than 800 diseases and disorders. Only in the Nursing Diagnosis Manual will you find for each diagnosis subjectively and objectively – sample clinical applications, prioritized action/interventions with rationales – a documentation section, and much more!

All-in-One Nursing Care Planning Resource – E-Book: Medical-Surgical, Pediatric, Maternity, and Psychiatric-Mental Health

Includes over 100 care plans for medical-surgical, maternity/OB, pediatrics, and psychiatric and mental health. Interprofessional “patient problems” focus familiarizes you with how to speak to patients.

Other recommended site resources for this nursing care plan:

Other nursing care plans for cardiovascular system disorders:

Recommended journals, books, and other interesting materials to help you learn more about hypertension nursing care plans and nursing diagnosis:

Matt Vera, a registered nurse since 2009, leverages his experiences as a former student struggling with complex nursing topics to help aspiring nurses as a full-time writer and editor for Nurseslabs, simplifying the learning process, breaking down complicated subjects, and finding innovative ways to assist students in reaching their full potential as future healthcare providers.